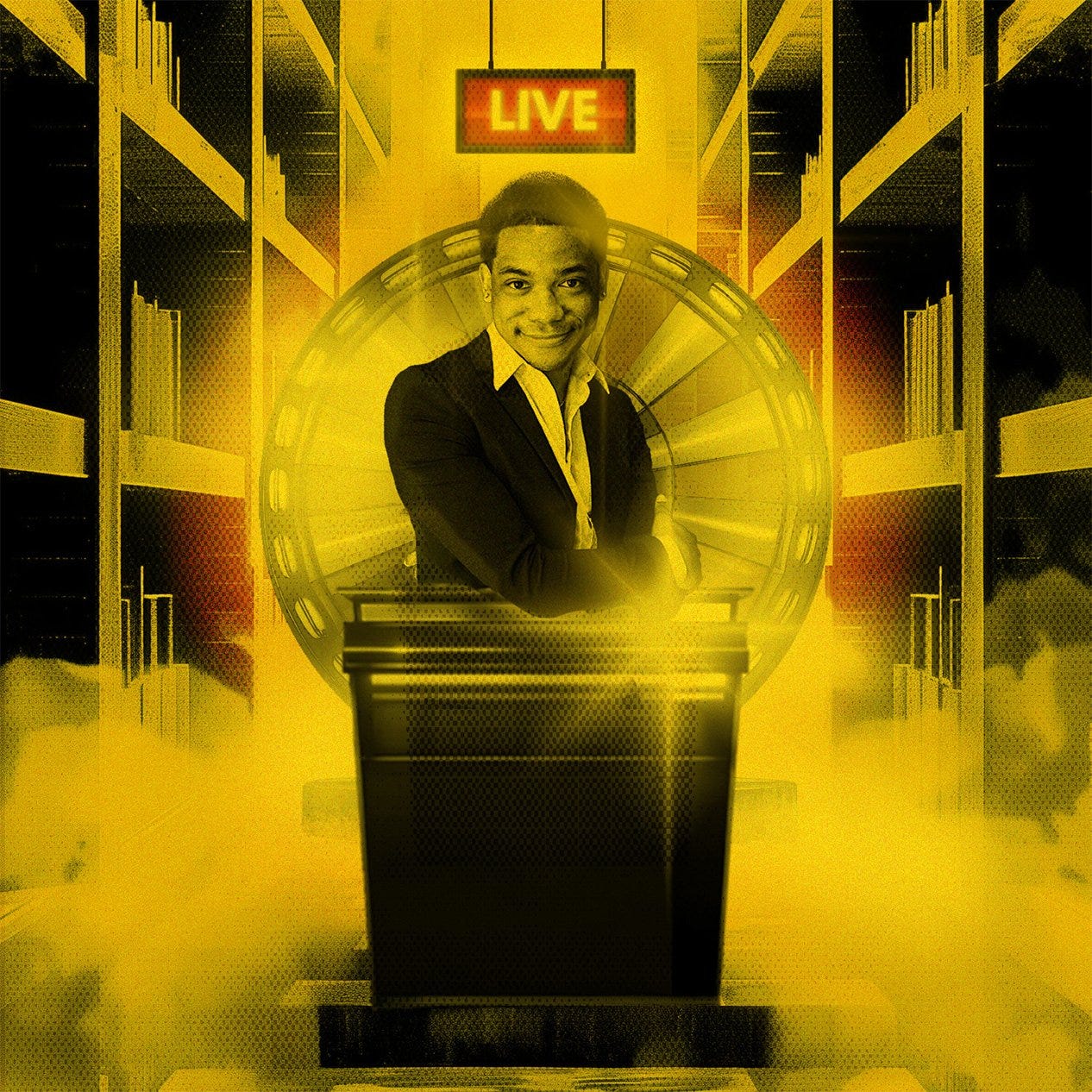

Black-Led Broadway Shows Are Driving A Billion-Dollar Comeback

As the Tonys approach, the industry’s biggest night is a chance to ask who gets the spotlight and who built the stage. And no one embodies this more than Audra McDonald.

I saw Audra McDonald in Carousel, the Cameron Mackintosh revival with colorblind casting. It was one of the first plays I loved as an adult. This was the ’90s. Seeing a Black woman fully inhabiting a classic Rodgers and Hammerstein role shifted the chemistry in my brain. It was more than that; it was her voice, soaring above the chorus. She showed her acting chops opposite Diddy, yes, Sean Puffy Combs in Raisin in the Sun.

If you’ve heard my work before or follow my Substack, Vanilla is Black, you know the intersection of race, culture, and economics is where I like to look. Broadway is where race, money, and meaning collide—all in the confines of a black box.

I’ve long admired Patti LuPone, but never quite loved her. She’s known as much for her verbal pugilism as she is for her vocal abilities. I saw LuPone in Sweeney Todd at Chicago’s Ravinia Festival. It was one of her truly transformative performances in a career full of them. She’s a diva. She’s brilliant. She knows it. She’s Patti LuPone. And yet, when you read the recent New Yorker profile of her, you realize she seems blithely unaware of her… self.

Yes, Patti LuPone has battled some of the biggest and worst male egos in theater history. Her longevity is a sign of stamina and proof that she’s won. In the New Yorker, LuPone proclaims, “People ask, why am I a gay icon? I think they see a struggle in me, or how I’ve overcome a struggle.” Fair enough. But struggle does not excuse ignorance.

The New Yorker Profile That Says Too Much

In the New Yorker profile of LuPone, it’s clear she’s lived a life. She’s fought co-stars, showrunners, and even audience members. She’s snatched phones, cursed out maskless patrons, and turned nearly every outburst into a meme. I want you to picture what might happen if a Black actress did just one of those things.

In the article, LuPone talks a lot about other women, especially Black women, with a superiority that’s hard to ignore. She was born in Northport, New York, which, even today, is less than 3% Black. While she’s seen as a New Yorker in every sense, it’s not hard to imagine she escaped the racial attitudes of mid-20th-century Long Island.

Of Audra McDonald, LuPone said, “She’s not a friend. That’s typical of Audra.” And of veteran actress Kecia Lewis, who called her out for noise complaints during Hell’s Kitchen, LuPone snapped: “She’s done seven shows. I’ve done thirty-one. Don’t call yourself a vet, bitch.”

“American theater gives Black women the finger every single day.” Carla Stillwell

Following the backlash, and a letter signed by 500 artist disinviting her to the Tony’s, LuPone issued a public statement: “I’m sorry if I offended anyone with my comments. I have nothing but respect for Audra McDonald and Kecia Lewis. If my words suggested otherwise, I regret it.”

To make sense of the dynamics at play, I spoke with Carla Stillwell. She grew up in Chicago’s South Shore and has spent four decades working in American theater as an actor, writer, director, and educator. She’s the founder of the Stillwell Institute for Contemporary Black Art and teaches in the theater department at DePaul University. Her work focuses on developing new work by Black artists and pushing the field past its reliance on white audiences and white approval.

“Anybody who has done one show on Broadway is a veteran. Go argue with your mom,” Stillwell told me. “People don’t know the work it takes to be integrated into that kind of high-level musical. To be physically and vocally trained just to be in the room. To dismiss that is so disrespectful.”

Kecia Lewis is a Broadway veteran who’s approaching legend status herself. She originated roles in Big River and Once on This Island, and brought down the house in The Drowsy Chaperone and A New Brain. She has worked quietly and consistently, without the fanfare her talent deserves. Her first Broadway role was when she was 18. The show was Dreamgirls, the original production.

Stillwell wasn’t surprised by LuPone’s condescension. “American theater gives Black women the finger every single day,” she said. “Patti LuPone has had twice as many opportunities as a woman like Audra McDonald or Kecia Lewis. Not because she’s not talented—she is—but because the work was created for her to flourish in as a white woman. There are at least eight Black women who could smoke her ass, but they were never given the chance.”

Lewis’ performance in Hell’s Kitchen is a reminder: in 160 years of Broadway, only ten Black-written musicals have been produced. When they are produced, Black plays are rarely revived, while new plays by Black writers struggle to get financing. And when Black actresses do break through, they often have to endure constant dismissal.

The reality is: Black plays are rarely revived. New plays by Black writers struggle for financing. And when Black actresses do break through, they often have to endure constant dismissal.

“Black women are the largest spending power in this country after white men. We’ve always been the revitalization of any industry on the brink. Broadway’s comeback? That’s us.” Carla Stillwell

Black Excellence Pays Dividends

Broadway's 2024–2025 season reached a historic high, grossing a record-breaking $1.89 billion and drawing 14.7 million attendees, according to the Broadway League. It marks the highest-grossing season in recorded history. Broadway has had an amazing economic recovery post-COVID. That recovery hasn’t been based on revivals or tired old greatest hits. It’s been Black-led productions like MJ the Musical, Fat Ham, and Ain’t Too Proud. These are new stories with new audiences that have helped fuel the comeback. Baruch College and Forbes report Broadway contributes an estimated $14.7 billion to New York City's economy and supports approximately 96,900 local jobs.

This resurgence is explored in my recent Forbes article, "Black-Led Broadway Shows Are Driving A Billion-Dollar Comeback," which highlights the pivotal role Black women have played in making this Broadway season one of the most successful in history.

Stillwell puts it more bluntly: “Black women are the largest spending power in this country after white men. We’ve always been the revitalization of any industry on the brink. Broadway’s comeback? That’s us.”

Before Audra, There Was Stephanie

Audra McDonald is the most decorated Broadway actor in history. She has won six Tony Awards, two Grammys, and one Emmy. McDonald was a star at Juilliard, where she trained as a soprano. If you’ve watched a PBS Great Performances, you’ve seen her swing effortlessly from Shakespeare to Sondheim to Mahler. McDonald’s performance in Porgy and Bess helped rake in $2.6 million in one week. Gypsy grossed a record-breaking $1.89 million the week ending January 19, 2025, and has earned over $36 million to date—all without the draw of a Hollywood name. With her 11th Tony nomination this year, McDonald’s streak continues. She’s the only performer to win in all four Tony acting categories: Lead and Featured, Musical and Play.

As Carla Stillwell put it, “One of the least problematic people in entertainment? I’ve never heard a dark or nasty word about Audra McDonald.”

“That woman is highly unproblematic. She comes to work to work.”

Stillwell herself is continuing to shape the future of Black theater. She is directing the world premiere of Black Bone, a satirical fantasy by Tina Fakhrid-Deen, at Definition Theatre in Hyde Park. The play, which runs from May 30 to June 29, 2025, follows a group of Black academics at a predominantly white institution who discover that one among them is "passing" as Black. This production is part of Definition Theatre's Amplify Series and is one of the few full-scale productions staged on Chicago's South Side, highlighting the importance of diverse storytelling in underrepresented communities.

The Standard Is Profitable: Black-Led Shows Are the Future

Broadway keeps treating Black-led shows like risks. But the numbers tell a different story. The Wiz ran for four years and launched a major motion picture. MJ the Musical is a box-office juggernaut. Fat Ham won the Pulitzer and proved that Black stories can be avant-garde and bankable.

Stillwell believes the way forward isn’t safe revivals. “Theater has to stop pandering and start developing new Black writers, Black composers,” she said. “The successful stories aren’t safe. They’re honest. We don’t need another revival. We need new work that isn’t shaped by white comfort.”

Go back even further, and you’ll find Ethel Waters one of the first Black women to star in a Broadway play. Her 1939 performance in Mamba’s Daughters made history. But backstage, she had to use a separate dressing room. Waters became the highest-paid Black performer of her time, yet producers were still afraid to put her front and center for fear of white backlash.

I interviewed Tiana Kaye Blair, director of Trouble In Mind, for NPR a few years ago. During rehearsals, she encapsulated the central tension: theater has to balance pushing audiences and keeping them comfortable.

She said: “Are you working to create something new that will then, in turn, do something new for audiences?”

Broadway’s future doesn’t rest on legacy revivals. It rests on voices like Blair’s.

Audra McDonald doesn’t need to clap back. Her resume is a read and a mic drop. I would rarely attempt to speak for Black gay men. Today I will, “We got you, Audra.” On the eve of Pride month, the Black gay world speaks with one voice:

Dear Patti, take several seats.

Everyone else, enjoy the Tonys.