Remembering Elie Wiesel: Souls on Fire, Memory, and Finding My Voice

How a Holocaust survivor’s words became a shield for a Black, gay journalist

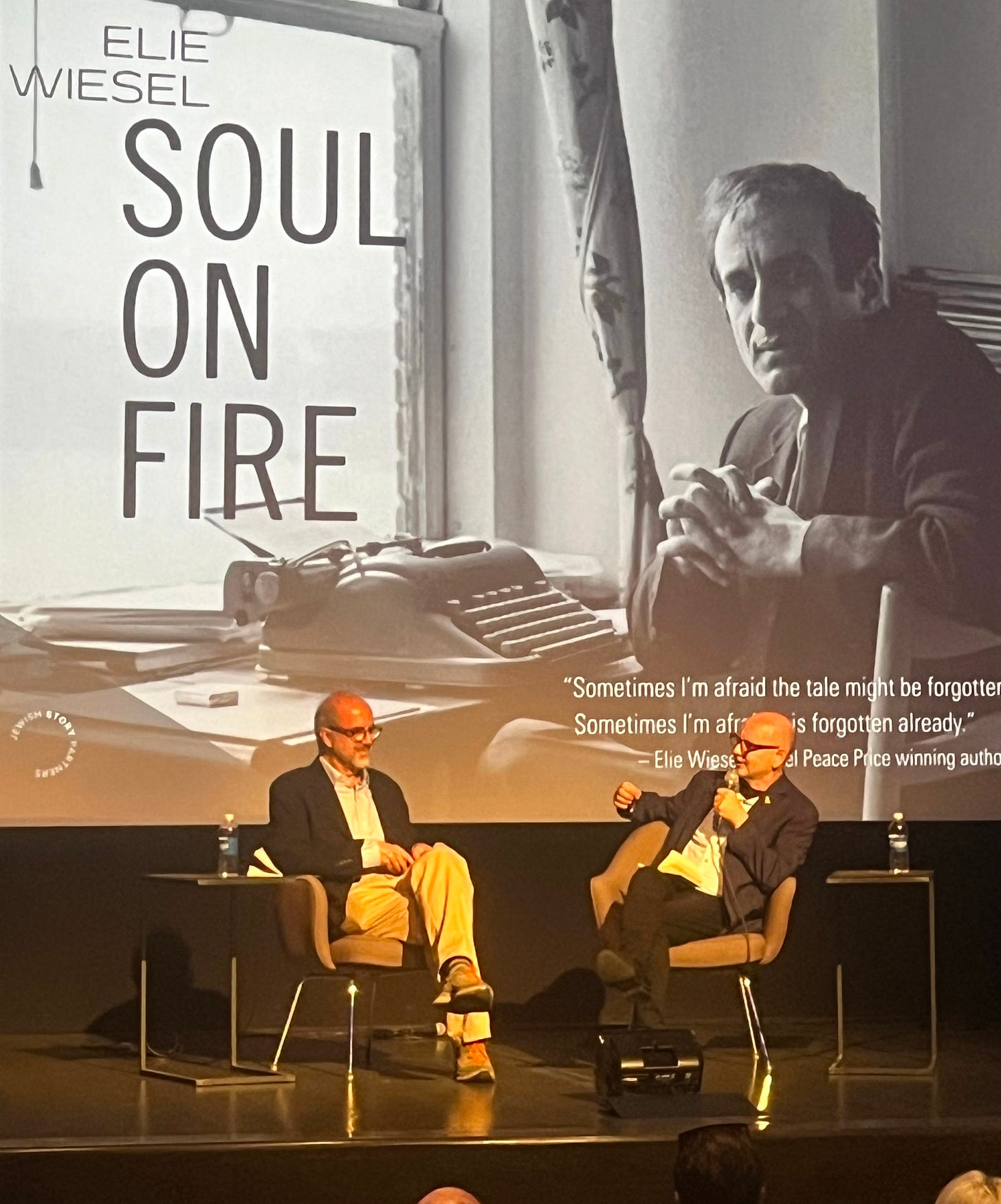

April 24th, 2025, was Yom HaShoah, or Holocaust Remembrance Day, in Israel and many Jewish communities worldwide. It also marks the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. To mark the occasion, I attended the L.A. premiere of Souls on Fire, a film by Oren Rudavsky about the life of author, activist, and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel. The movie is sans narrator and told through Wiesel's words using interviews and animation. It rightly centers his widow, Miriam Wiesel, who died earlier this year. Marion Wiesel translated nearly all of his work.

Hearing Wiesel’s voice brought me back to Boston University, when I would attend Wiesel’s lectures in the George Sherman Union. The film reminded me of why I found myself in the orbit of Elie Wiesel, his staff. Wiesel’s office was staffed by Martha Hauptman and Ondine Brent, among others. One of the key themes of the film was finding your voice. I was featured briefly in the film, which is making the festival rounds. It’s expected to be part of the American Masters documentary series. It was at Boston University that I began to find my voice. I was inspired in his classroom to become a journalist. I was aided and encouraged to complete that dream by his assistant, Martha Hauptman.

I wrote this essay on Elie Wiesel’s death in 2016. It appeared first on NPR’s Code Switch, edited by Alicia Montgomery. It’s one of most popular pieces. I wouldn’t change a word:

(previously featured on NPR)

In the late '80s, when I was in the fifth and sixth grades, my school librarian took a special interest in me. One day our assignment was to do a book report, and Ms. Newton pointed me toward the biography section. Being the lazy kid I was, I picked out the thinnest book I could find. Barely a hundred pages, I thought. I can knock this out. I only had to skim it, I thought, and I'd get an A. The book was Night by Elie Wiesel.

I was right about one thing. It was a quick read. That was it.

I'd read stories with all kinds of protagonists — Laura Ingalls, Huck Finn, even The Diary of Anne Frank. Having read that last one — and having watched a few made-for-TV movies about the Holocaust — made me think I was already a bit of an expert on that experience.

But as I sat up reading, Night stirred something deeper in me. Maybe it was the simplicity of the story. Maybe it struck me because of how bookish and isolated and weird the young Eliezer was. Just like me, he was concerned with books and theology. Being Jewish made him vulnerable in a way that I understood. I knew, as a black child in Chicago, I lived in an isolated community where I was deeply loved. But with the racial turmoil of the time, I also knew there were hostile forces all around me.

The more I saw myself in Eliezer, the more Night frightened me. It was the language, the simplicity of his prose, the immediacy of the horror, the distance he seemed to feel from himself. To say the book changed my life would be a cliche and not entirely true. But if I could be so much like Elie, I reasoned then, the life I loved could be taken from me. The book made me aware not only that suffering existed elsewhere, but that my world was fragile as well. I imagined being removed from South Shore, from my church and school, from my family. The Holocaust felt very present. He made it personal. That stayed with me for years.

So when I was applying for college, and got a shiny brochure from Boston University, I remember turning the page and seeing Elie Wiesel's picture. That the author existed in the real world seemed magical. That, and a few well-placed pictures of the crew team, and I'd decided. Boston University not only had Boston going for it; it had Elie Wiesel.

I realized during orientation that one doesn't just take a class with Elie Wiesel; he picks you. And it was much easier to get in if you majored in religion, philosophy, or something like that. So I switched majors. I entered BU to study communications, but changed to religion and history. I put my name on the list, and in my junior year, I got the note that I'd been accepted to take his course on memory, subtitled "Writers on Writing." Each of the 16 or so students had to present a book. I picked The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison.

If I had expected this to be some easy survey course with a lightweight, celebrity professor, the surprise would be mine. On the first day of class, Professor Wiesel breezed into class and quickly destroyed my ideas of what he'd be. He doffed his jacket and rolled up his sleeves, and immediately started with the jokes. He was trim and stylish with his perfectly knotted tie and lapel pin, which I assumed was for the French Legion of Honor. Professor Wiesel was goofy, cute, and super funny, kind of like Jackie Mason on Valium. Frequently, while speaking, he shoved his wild tuft of hair to the side. His vanity and arrogance were on full display; so were his sensitivity, generosity, and humor.

Memory, he said, wasn't just for Holocaust survivors. The people who ask us to forget are not our friends. Memory not only honors those we lost but also gives us strength.

"The relationship between teacher and student is sacred." Those are the only words I remember. He informed us that his office hours were mandatory. And we were expected to schedule our time with him. This would be a rigorous class. We would be graded on the quality of our participation, our presentation and the final.

As the weeks went by, the time to present my book came up. "Why did you choose the black book?" I thought to myself. I was already the only black guy in the class. Why draw attention to it? I'd had enough of being the only black whatever at my predominantly white Jesuit high school to be extremely wary. As I read Morrison's debut novel, I was struck by how beautifully she captured the feelings of being not just black but dark. Unlike Night, this book took no imagination on my part. I knew it. I felt it. I'd lived it. Pecola Breedlove, the black protagonist who dreamed of getting blue eyes, was a girl I knew. Sometimes she was me.

When I began my presentation, and looked down at my notes about skin color, race, and blackness, I was overcome. I glanced at Wiesel, who looked at me with encouragement. I immediately began to cry — not a Denzel Washington dignified Glory tear, but a full-on Oprah "ugly cry."

Without memory, there is no culture. Without memory, there would be no civilization, no society, no future. Elie Wiesel

What strikes me about that course is not that I cried. It's the environment he created in the class. It was a collective sense of empathy. You see, though Wiesel was a celebrity professor, he didn't act like a celebrity professor. If you could get over the Nobel Prize thing, he was easy enough to chat up, especially when he was waiting for his car to the airport.

During our first office hours, Professor Wiesel turned back to that moment in class. We spoke about race. This was pre-Million Man March and O.J. trial, but post-Los Angeles riots. In my college youth, I was quick to want to "get beyond" race. I apologized for what I thought was an unmanly outburst in class. I admonished myself for "not being able to get past it."

I remember him leaning in and asking why I would want to forget.

Memory, he said, wasn't just for Holocaust survivors. The people who ask us to forget are not our friends. Memory not only honors those we lost but also gives us strength. In those office hours, he gave me a shield, practical words and thoughts that would help me, a gay, Nigerian, Catholic journalist. He gave me tools that would aid me in an often hostile world. Over the years, I have found myself quoting Professor Wiesel to white people who want me to "get over race." "That's old." "It was a hundred years ago." But Professor Wiesel had been emphatic: Nothing good comes of forgetting; remember, so that my past doesn't become your future.

Sonari, this is so beautiful. I never heard or read this essay before. Thank you for sharing such a powerful piece and giving us a window into who Elie Wiesel was like as a person and as a teacher.

Thanks Sonari for sharing your beautiful essay. And lovely seeing you at the screening. Your presence in the film was priceless.